Roger Ballen

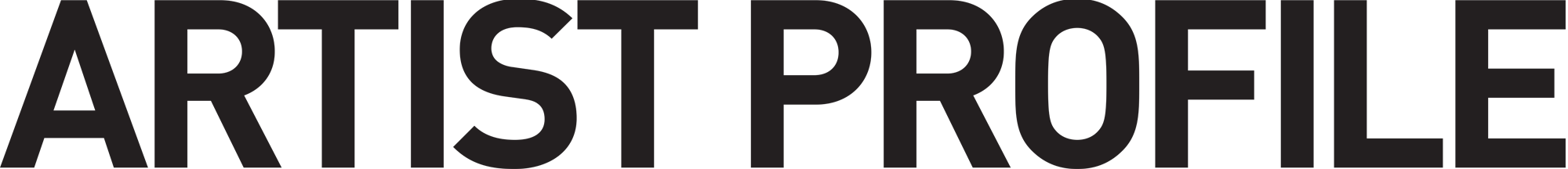

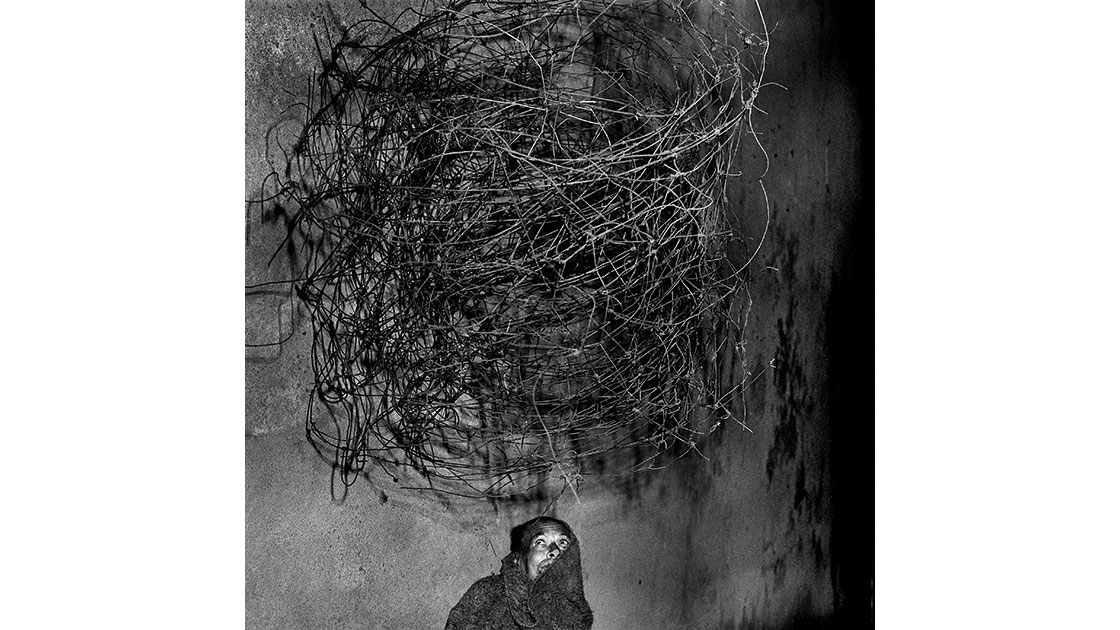

Photographer Roger Ballen, using the same Rolleiflex black and white film camera for the last 30 years, has created a vivid, imagined, sometimes disconcerting world filled with images of wild animals and people at the very margins of society – many of which he says are, in a way, self portraits.

Internationally renowned photographer Roger Ballen was born in New York in 1950, and has lived in Johannesburg, South Africa, since the 1970s. Ballen’s striking black and white photographs are constructed in a unique manner blending performance, drawing and sculpture. He combines subjects and objects within the frame in an ambiguous and often surreal manner, and the result is at once haunting and beautiful.

Ballen has always been interested in people and places on the margins of society, from the inhabitants of rural villages in South Africa, which he photographed in the 1980s, to the Asylum of the Birds depicted in his latest series. While in early works Ballen collaborated with his subjects to create works focusing on individuals and their personalities, over time the artist has moved towards a deeper exploration of his own psyche, and of humanity in general.

What started your interest in photography?

My mother worked at Magnum in the 60s and worked with some of the most famous photographers in the world, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Elliott Erwitt and André Kertész. Then in the late 60s she started one of the first photo galleries in the United States, in New York City, and was the first person to sell Kertész photographs as well as photographs by people such as Edward Steichen and Cartier-Bresson. So as a young boy I met these people and she passed on her enthusiasm to me. I started taking pictures when I was 16 or 17 years old. My graduation present from high school at age 18 was a Nikon FTN, and I started taking serious pictures in 1968.

And you still prefer a film camera, is that correct?

Up until now all my pictures are film, although I’m sponsored on the digital side by Leica and they’ve given me a monochrome and I’ve taken some great pictures with that as well. But all the photographs I’ve taken for all the previous series have been with a Rolleiflex 6cm x 6cm film camera. I see myself as the last generation of photographers who grew up with black and white film. It’s been part of my life, a part of my history and I really feel attached to it. It’s just a personal preference, but I certainly understand why people would want to go to digital; it’s cheaper, easier and the quality is getting so good that I think for an average person it doesn’t make sense to use film. I grew up with it but there are significant drawbacks to film over digital now.

There must be positives as well?

Yeah the positives are basically quality, for a big size negative you get very good quality. And it’s the whole way of taking pictures, it’s the perception of the world, it’s a consciousness of the world when you use film – you feel like whatever you do has some value, and I think that rubs off on the kind of pictures you take. It’s not like flipping on the internet from picture to picture, there’s a concreteness about it. I think if you take pictures on a phone camera and you’re paying less than one cent a shot, the shot doesn’t have intrinsically the same value in a way. Today’s my birthday, I’m 65, and even at age 65 when I get the contact sheets back I’m still excited.

How many shots do you usually need to take to get the right shot?

It really varies, you could take 10 rolls of film and never get a good picture, and sometimes you take one and you’ve got a great photograph. It’s unpredictable. Sometimes the difference between a great shot and a bad shot in a lot of my photographs is just where the eyelid is on a blink, that’s what makes the picture.

And you regularly photograph animals and people – I imagine that adds another element of spontaneity?

Yes, you’re absolutely correct about that. For the last 15 years there have been a lot more animals in the pictures. It’s unpredictable with the animals what they do.

I imagine they’re not trained?

No, never trained, they’re wild animals.

Do you like the unpredictability of that?

I think spontaneity is a very important part of photography and always has been. That’s why I never plan my pictures. When I get to a site I work on them, but it’s the spontaneity of the moment in many ways that separates a great photograph from a mediocre one. A lot of people involved in contemporary art trying to use photography don’t understand this. They can conceptualise something but the thing that drives most pictures home is the fact that when people look at them they believe it’s a special moment.

So you don’t plan your shots before you take them?

I have what I say is 65 years of planning. It’s not a matter of just going in there and putting elements together, it’s a whole consciousness that’s evolved over decades of being able to create a world that has a life to it, an organic-ness, a deeper meaning. It’s a science and an art. It’s like juggling – when I was 18 I could put two balls in the air, now I’m putting 50.

However your backdrops have become more worked on – drawing and sculpture have become more prevalent.

It’s evolved over a long period of time. If you go back in the history of my work, the drawing and the line-making started to appear 20 to 25 years ago, and it gradually, gradually moved into the picture. It became a material part of my photography in 2003, when portraiture in the photograph gradually dissipated, and drawing and sculpture started to dominate the fundamentals of the work. It took a long time to get there but it continually evolves.

In your recent series, Asylum of the Birds, mannequins and masks take the place of the human figure.

Yes, that’s correct, there’s more non-living human figures in the pictures, and that creates another synthetic within the nature of the image and the way people view the image. If you’re using a mannequin then the reality around the mannequin and the integration of the synthetic around the mannequin have to be different than if it was a live subject and vice versa.

When you do use human subjects what role do they play in your images? Do you guide them or is it a collaborative process?

They stand there, and do things. Some may say look at me, but while they’re showing me their hand I may be looking at their foot. It’s no different than Picasso or one of the great artists – you deal with the subject. The subject may be sitting there, but the photographer is transforming the reality, so ultimately what you are looking at is reality transformed by Roger Ballen through a camera lens and through his brain. Nobody else can take the same pictures as me, I’m convinced of that. I have a particular style, and that’s it. Because it’s taken me years and everybody’s brain is different. I can’t paint like Picasso. I can’t take pictures like Avedon. I have my own style.

Do you get to know your subjects?

Yeah, a lot of times I’ve known people for a number of years. Today I must have got about 50 birthday wishes from my subjects, so I’ve had a long relationship with a lot of them. But sometimes my greatest pictures take place with someone I only met for five minutes and then never saw again. My new ‘Outland’ film gives a feeling of the subjects. It’s an excellent film and it’s going a bit viral, I’m really happy with it.

Film seems to be coming more important to your practice?

I think making installations and sculptures and film is an important part of what I do, but I still see my core artform as black and white film photography. I wouldn’t do documentary films if I can help it. I see the last film as an artwork, but it really is the best way of getting your work out there. The Freeky video (‘I Fink You Freeky’) got over 60 million hits – so many people got to know my work all over the world through that. You can’t achieve that with book sales. I don’t necessarily do it for marketing, but it really is the way to get your work out there as a still photographer.

But your books remain important to the way you work?

The books have always been the most important thing in my career, they usually take about five years to produce and my work is always geared towards books. To finish a book you start a project, and you finish a project, and you package a product, and people can then comprehend the time you spent on a project. There’s no way you can be a Cartier-Bresson in today’s world anymore, it’s hopeless.

What are the major influences on your work?

The main influence by 90 per cent is my own photographs. That’s how I learn. Living in South Africa is probably worse than living in Australia in the sense that you’re more isolated from mainstream culture, so most of what I’ve been developing in my photography over the last 30 or 40 years has really mostly come about through my own hard work with my own pictures. I had a good education, I read a lot, and I understood theatre. I’ve said that ‘Outland’ was very influenced by Beckett and Pinter and Ionesco, but at the end of the day for the last 30 years it’s just hard, conscientious work and reflecting on my own pictures that take me forward.

I can go to the best photo exhibition in the world and go back and take photographs and it doesn’t help me at all. What’s it going to do? The key to a work might have been something that happened at six years old that I remember all of a sudden. Who knows? It’s not possible to understand how the human mind works. Or how creativity works, and how these pictures come about. It’s a very complex interactive process that nobody understands in any real way as far as I can see. It’s beyond words.

You have described your works as self-portraits…

Reflections of my own psyche, my own existential anxieties, my introspections, my contemplations of the world. They’re the way my mind expresses itself in various ways and to try to understand itself in some way. And hopefully the pictures help others to do the same.

A lot of your work focuses on people and places at the margins of society; what led you to this?

I think I’ve been there for a long time. I did a film in 1972 about somebody who looks like somebody in my recent film. So I don’t know what led me there. I can’t really know. They hit something deep inside that made me want to follow through with it more. I can’t really say why, it’s not possible, it’s like saying why you like yellow over green.

You’ve started to exhibit sculptures and drawings alongside your photographs; do you think this adds to people’s perception of

your work?

Definitely. It’s like the videos – it presents a parallel reality that expands the aesthetic of what I do. It provides multiple mirrors into my aesthetics, into my mind, into my art. I think it’s a good thing. I spend most of my time taking black and white photographs, which are an integration of drawing, painting and sculpture through photography. If I were living in Berlin perhaps I would be exhibiting more sculpture and drawings because it would be easier to get them around, but living down here it’s a big job to transport everything, so I don’t keep these things as much as I should.

You have an exciting upcoming project in Sydney; can you tell us a bit more about that?

I’m very much looking forward to my exhibit at the Sydney College of the Arts. It looks like a fabulous space, the basement there was like a prison or something – it will be a great place to show photographs and make an installation, and I think there’s some floors above ground where I can also show my work, so I’m hoping it will be a multi-dimensional exhibition. I’m really looking forward to it.

I’ve had some great shows in Australia. I had a show at MONA last year and previously at The Art Gallery of Western Australia and the National Library at Canberra, and I was part of the Sydney Biennale, so I have a good following in Australia and I really like the country a lot. I’m so pleased that I can get back there and do something again.

A new and expanded edition of ‘Outland’, featuring 45 previously unpublished pictures from Ballen’s archive, has just been released.

An exhibition of Roger Ballen’s work, curated by Colin Rhodes, will be presented at the Sydney College of the Arts around the time of the 20th Sydney Biennale in 2016.

www.rogerballen.com

www.thehughesgallery.com

Courtesy of the artist and The Hughes Gallery, Sydney