Books & Culture

Nidhi Chanani’s Graphic Novel ‘Pashmina’ Is Part of an Important New Genre

Comics and coming-of-age novels are a perfect match, especially for underrepresented voices

I t was only as recently as 2006 that Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese became the first graphic novel to be nominated for a National Book Award. That book, about a Chinese American boy’s struggles with his identity, drew comics for young people from the the fringes to the mainstream.

A little over a decade later, Vulture declared graphic novels for young readers to be the “most important sector in the world of sequential art.” Graphic novels and memoirs, particularly those created by women, tap into the power and options in the combination of visual and written stimulation to relay stories across genres and ages.

My own graphic novel consumption has increased to include titles such as This One Summer by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, Ms. Marvel, Vol. 1: No Normal by G. Willow Wilson and illustrated by Adrian Alphona, The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui, and excerpts of Mira Jacob’s forthcoming graphic novel, Good Talk: Conversations I’m Still Confused About. I grew up reading comics — from Archie to Amar Chitra Katha — but today’s graphic novels mean so much more, especially those by marginalized women. As cliché as it sounds, it’s validating to see women like me in comic panels.

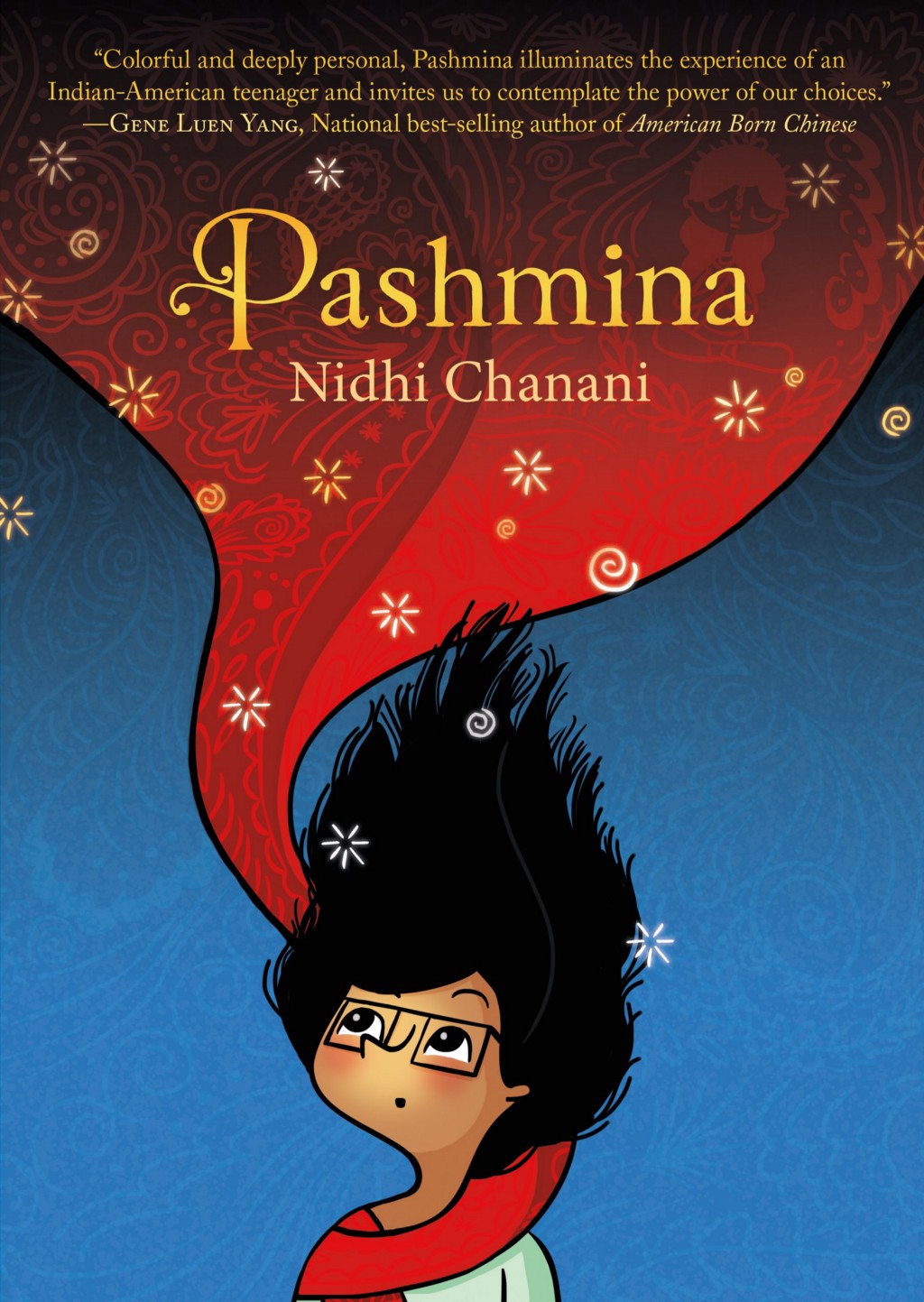

The latest addition to the canon of sequential art books — and specifically the subset that is written and/or illustrated by people of color and indigenous people — is Pashmina (First Second, 2017) by cartoonist Nidhi Chanani.

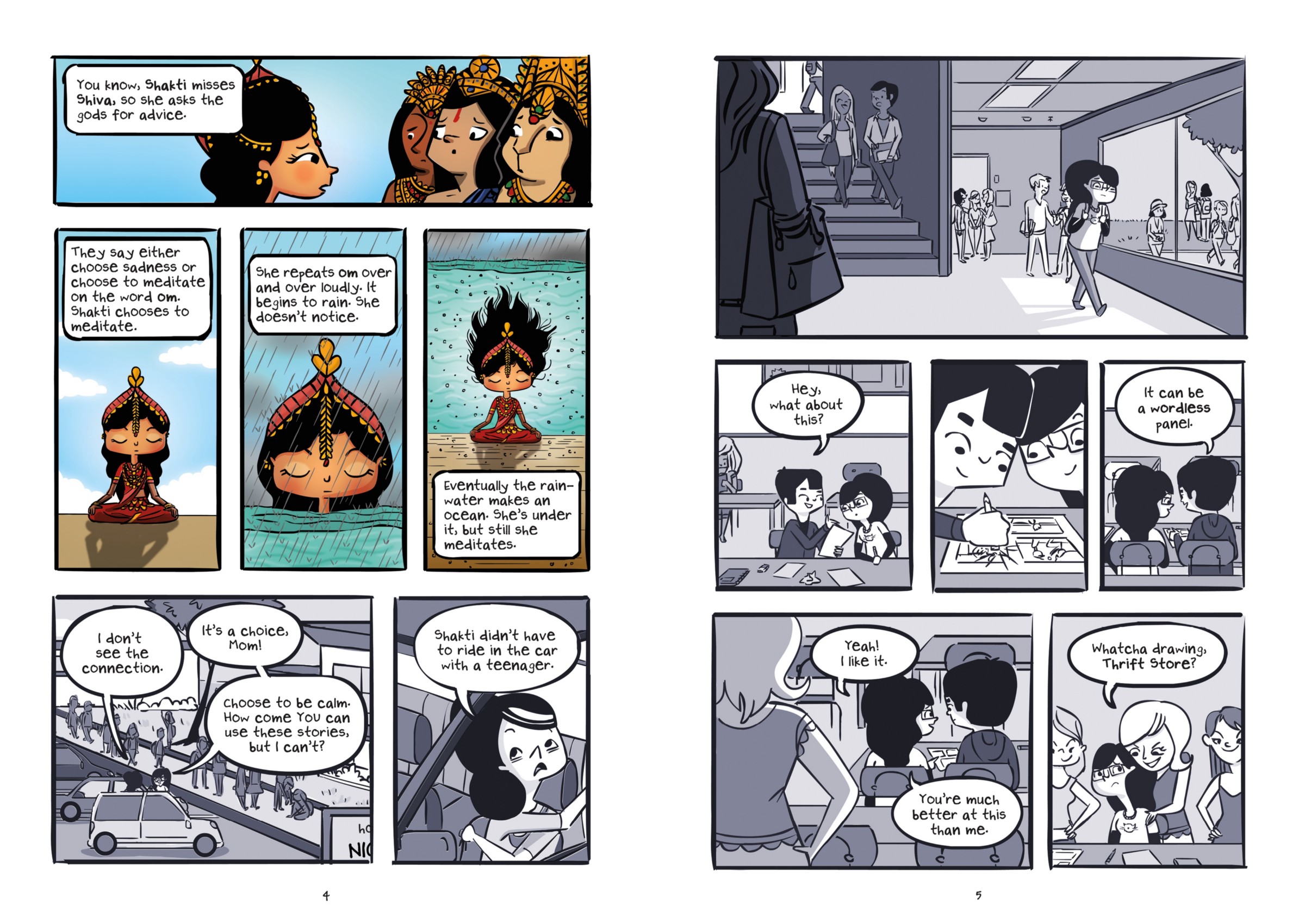

Pashmina is an unabashedly feminist tale about Priyanka “Pri” Das, a comics-obsessed teenager in Orange County, California. It features her mother, who won’t speak of Pri’s father or India, the country her mother left and has vowed never to return to; Shakti, the powerful Hindu mother goddess; and a mysterious shawl that transports Pri to the India of her imagination when she wraps it around her shoulders.

Chanani’s illustrations dramatically alternate between black-and-white (when Pri is in the United States) and full-throttle color (when Pri is in India). In the course of this first-rate adventure tale, Pri learns about women’s choices — especially her mother’s — and living without fear. I talked to Chanani about magical realism, South Asian families, and how Pashmina came to be.

Pooja Makhijani: You are well-known for your short strips, yet this is your first full-length novel. In the course of writing and illustrating this book, what did you learn about sustaining plot and character?

Nidhi Chanani: On one hand, I learned things around the art — and how to keep the character consistent page after page. I also learned a lot about body language and positioning to convey emotions. In the place of words, I utilized facial expressions and positioning to give the reader insight into my characters’ emotions.

On the story side, I learned to know my characters. It sounds simple but writing a lot about Priyanka, her mom, and her uncle allowed me to fully realize them on the page. The reader may never know that Priyanka hates bubble gum, for example, but I do, and that makes her grounded in reality.

And finally, throughout the process, I learned how to parse out information: to utilize the “page turn” to keep revealing parts of the story in pieces, to keep the reader engaged in Priyanka’s journey.

PM: Pashmina explores the ways women are constrained by patriarchy. Why is this story about the intersection of power, community and identity best told in comic form?

NC: I think the question sometimes presumes that comics is better than other mediums. But it’s simply another medium to me. I do believe it has merits that are different than others. I believe there are access points to comics that traditional prose cannot touch.

I don’t limit myself to comics. I want to explore all mediums. And within anything, I do want to challenge things and hopefully create dialogue and a narrative that goes beyond the page.

PM: Priyanka is the daughter of a single mother, a family structure rarely represented in young people’s literature of the South Asian diaspora. Why was this representation important to you?

NC: There are family dynamics that are rarely seen from many communities — including ours. I wanted to work within a story that isn’t often seen but is still relatable.

Although I grew up in your traditional Indian family (mother, father, sibling), we had tons of problems. Those problems, as much as we tried to hide them from our community, came to define us. My mom eventually left my dad.

She was ostracized from the Indian community.

I saw what a difficult time my mom had to move within our community without support. In an instance it’s a triumph for women to stand up for themselves, but the community does not support moving past the traditional roles. It adds another challenge.

I wanted to explore what having a single mom from the beginning would mean for Priyanka. To have that as a norm within her life, but to have unanswered questions. I feel that she had respect for her mother, while also not completely understanding her. Then through the book, she gains the understanding she was missing.

The Best of This Year’s Small-Press Comics

PM: Priyanka’s “India” is one of monkeys and elephants and other such touristic images of India, yet you are subverting these familiar visual tropes so that they no longer reinforce stereotypes. What was your intention in representing India in this way on the page?

NC: To put it quite simply, I wanted Priyanka, a teen who’s curious about her culture but not versed in it, to have a positive introduction to India.

I wanted her to be drawn into the amazing aspects of India, but to also indicate that there’s more. In many ways, Priyanka’s relationship with the fantasy India is one that many people have. I wanted to mimic that, while also giving context to why later, she chooses to visit the real India. My attempt to represent it in parts had to pay respect to that truth.

PM: There is an element of magical realism in Pashmina and, in those magical realist panels, the palate switches from black-and-white to color. Can you talk about this artistic choice a bit?

NC: I love India, and I wanted to represent India in the way I eventually came to imagine it. I also wanted to fully utilize the medium of comics.

I could’ve done the whole book in full color — which is great and those books are very welcoming to readers. But it was very early on that I wanted to add more impact to Priyanka’s story. In a visual medium, the use of color is powerful. It’s one that I feel I know and understand well, so adding another layer to the story through color — and the absence of — provided for a richness that I feel is the strength of telling this story through comics.

I love India, and I wanted to represent India in the way I eventually came to imagine it. I also wanted to fully utilize the medium of comics.

PM: Pashmina also contains a lot of religious iconography — the divine mother goddess figure.Where does your interest in this stem from? Are you a spiritual or faithful person?

NC: I was raised Hindu and I describe myself as a lapsed Hindu. I find that even though I don’t practice Hinduism, I have aspects of its spirituality in my life. I was very much like Priyanka growing up, where I dragged my feet at prayer time and questioned whether it made a difference.

Beyond my own interests, I felt that the pashmina had its own story to tell. And Shakti had a pressing need to connect with women. Who better to tell that story than her?

As much as there are religious components to Pashmina, I don’t think of that first. I really think of it as a feminist story, and I believe gods and goddesses are feminists.

PM: MacArthur Fellow and National Book Award finalist Gene Luen Yang introduced Pashmina as the first graphic novel wholly created (written and illustrated) by an Indian American. Did you write Pashmina with this awareness? How does that label — “first” — make you feel?

NC: Oh man! Yes, I was aware of that fact. I was aware of it as I wrote and drew every panel.

I was aware of it when I chose to add Hindi into the text and refused to add asterisks within the pages. (My publisher, to their credit, never asked me to). I was aware of it when I chose how to represent India, Kolkata and every character.

I stressed about all of it, honestly.

But in my best moments of writing and drawing, I forgot that I was a “first” anything. I just approached it as my story. My chance to write and create the best story I could.

I think firsts are hard, but important. All I can hope is that Pashmina does well enough to pave the way for more Indian American graphic novels and comics. The responsibility is not one I asked for, but given that seat, I know that how I perform and how my book performs will impact others. I do my best to be intentional and aware.