Le fabuleux destin d’Amélie Poulain

Director: Jean-Pierre Jeunet

By Roderick Heath

Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s 2001 film Amélie remains the highest-grossing French film of all time and a movie that pierced the cultural awareness of the English-speaking world as very few recent foreign-language films have managed. It was, and is still, regarded as a “feel-good” film par excellence, a label that is as often used as a pejorative as it is in praise, with some at the time of its release even stating that the film ran into trouble with some French critics because it courted that designation. Whether or not Amélie is simply a movie designed to elicit cheer in an audience demands we actually ask what, generically or even commercially speaking, a feel-good movie is and whether or not a feel-good film is necessarily simple. Because Amélie is surely not a simple or simplistic film, either stylistically or dramatically, in portraying a heroine pursuing happiness not only for herself, but also the people she may or may not know.

Geoffrey Mcnab, writing for The Independent newspaper, listed 25 feel-good films, including Saturday Night Fever (1977) for “mixing blue-collar realism with feel-good escapism.” The word “escapism” is particularly important, because it implies a removal from the actualities of life. Yet, many of the films Mcnab lists take a distinctive, real-world setting and face troubling facts of life, which suggests the feel-good template demands looking at those actualities, as painful as they can be, before providing idyllic relief and fulfillment. In Amélie, the shadows of depression, sexual frustration, jealousy, physical frailty, and the possibility of becoming entrapped by despair and rejection lurk as vividly for its fantasist heroine as for the people in whose lives she tries to providentially intervene. Whilst the film often seems to bend arcs of probability in flagrantly improbable directions, its grounding in immediate and troubling situations is consistent.

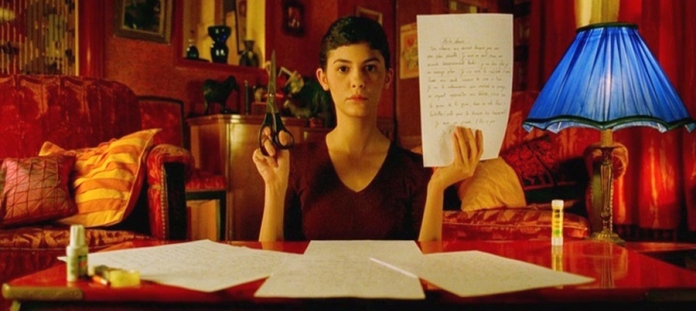

Amélie Poulain (Audrey Tautou) becomes a kind of performance artist specialising in making feel-good movies out of the lives of the people she knows. She arranges unlikely romances, conjures acts of moral reward and reprisal, falsifies great coincidences of fate, and tries to uplift and inspire hope in even the most isolated and forlorn of folk, all flourishes that can be associated with the ideal of entertaining films. She tries to step back from her actions, to maintain an almost godlike distance, and leave the recipients of her good deeds to bask in the glories of chance and fate that have benefited them. The concept of providence, of things that are meant to be, perhaps underlies some assumptions associated with the feel-good film, which seek to assure that things will indeed be alright, as if intended so. Mcnab’s article mentions Slumdog Millionaire (2008), in which small quirks of fate gave its hero the correct answers for a game show, until he is forced in the very last question to rely entirely on chance, and again wins: fate is quite literally on his side, but not in any fashion that is acknowledged by the passive heroes or presented with any irony by the filmmakers. In Mcnab’s top pick, It’s a Wonderful Life, George Bailey (James Stewart) is resuscitated by his guardian angel Clarence (Henry Travers). In Amélie, when the heroine arranges for Dominique Bretodeau (Maurice Bénichou) to rediscover his childhood trinkets, Bretodeau believes his guardian angel must have arranged it. Amélie casts herself in the role of magical sprite returning to people their lost childhoods and lovers, a one-woman conqueror of the vagaries of chance and fate.

Simultaneously, Jeunet’s filming presents a series of ironic discrepancies that reflect not only Amélie’s assumptions, imaginings, and desires, but also the film’s own purpose, beginning with the fact that filmmaking itself announces its godlike authority. Jeunet utilises an omniscient narrator (André Dussollier) and a flagrantly showy editing and photographic style that willfully digresses and explicates matters far removed from Amélie’s immediate perception, offering at will climatic details, deeply withheld personal fantasies, and characters’ memories. The narrator, and the director driving the movie, lay out with loopy concision those vagaries of happenstance Amélie battles, from offering up such details as the suicidal Canadian woman who claims her mother’s (Lorella Cravotta) life, to tracing the converging paths of various protagonists, to fateful moments and a series of what Jeunet called “positive and magical images.”

The fastidiousness with which the film outlines such twists of serendipity constantly confirms their improbability. Jeunet had utilised such narrative ploys before in his two feature collaborations with Marc Caro, Delicatessen (1991) and Cité des enfants perdus (1995), especially in a sequence in the latter film in which the central protagonists’ lives are saved by the intervention of coinciding events that tie together mice, strippers, and an ocean liner. Such storytelling dazzles with its invention, but also signals the directors’ knowing viewpoint by not merely contriving a happy ending, but offering the most contrived one possible. In Amélie, Jeunet deliberately dangles the threat inherent in chance, before then corralling the story toward a given end, much as Amélie conjures a series of absurd events that might have transpired to prevent her prospective boyfriend from making a rendezvous, in indicating how difficult getting from Point A to Point B in a world of infinite possibility can be.

Amélie’s own transformative imagination, which imbues everything about her with a visionary potential, is matched by Jeunet’s employment of CGI techniques to conjure an idealised, graffiti-free, nostalgically perfect Montmartre. When Amélie properly becomes a kind of filmmaker, recording fragments of wonder from the television for the benefit of the frail recluse Dufayel (Serge Merlin) the “Glass Man,” she edits together fragments of reality—horses running with cyclists, tap-dancing peg-legs—that evoke how often the world slips its own limits of credulity. Amélie, and the film around her, draw attention to the possibility of orchestrating chaos, and the enormous varieties of existence on Earth. As Amélie discovers, however, life does not obey all that she demands of it, and Jeunet refuses to suggest everything is correctable. The romance she helps stoke between hypochondriac tobacconist Georgette (Isabelle Nanty) and pathologically jealous café regular Joseph (Dominique Pinon) sees a brief interlude of comically intense romance soon give way to familiar patterns of behaviour; likewise, Amélie finds few of her interventions have immediate transformative impact.

Amélie herself, daughter to “a neurotic and an iceberg,” is, under her elfin bob, repressed—sexually and emotionally incapacitated and unable to engage directly with the world. She and Dufayel explore her ambiguities and faults through a stand-in, a figure in Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party” Dufayel paints over and over, who is defined by the fact her face is partially hidden by a glass. Hipolito (Artus de Penguern), the film’s only, actual designated artist, is a commercial failure who claims: “I love the word ‘fail.’ Failure is human destiny.” Hipolito’s creed throws into relief both Amélie’s dedication and her shortcomings. The best she can hope for is to offer moments of wonder for people, stimulating them through totemistic acts that are open-ended in their possibilities. As Amélie becomes a variety of artist, the film reproduces cultural tropes and popular and celebratory art constantly in a cornucopia of references: Impressionist painting, blues music (Sister Rosetta Tharp), French chanson (Édith Piaf), masked heroes (Amélie imagines herself as Zorro), Don Quixote, Looney Tunes cartoons, Citizen Kane (Amélie’s imagined obituary newsreel), and Soviet propaganda films. In one scene, Amélie watches Francois Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1961), which Jeunet’s directorial technique mimicks, particularly the fastidious voiceover in Jules et Jim, as well as the editing style and alternating emotions of its predecessor in Truffaut’s canon, Shoot the Piano Player (1960).

Jeunet’s structure thusly encompasses a vast array of cultural references not dissimilar to the way the apartment building in Delicatessan housed an array of classic French eccentrics. Dufayel’s self-isolation evokes both the works and lives of French Impressionists: he worships Renoir and suffers from a disease similar to that from which Toulouse-Lautrec suffered. His hermetic universe, shaky and brittle, is also repetitive and assailed, and cannot long countenance the intrusion of the garrulous, put-upon Lucien (Jamel Debbouze) and his less elevated references. “Lady Di! Lady Di!” Dufayel mocks him, before declaring: “Renoir!” Dufayel’s fixation with the glories of the past is both intensive and helpful and yet also as closeted and vulnerable as he is. He only uses his video camera to tell the time, until Amélie conjures for him more expansive visions. She doesn’t draw him away from his obsessions, but she does broaden his world. Likewise, his singular meditations hand Amélie vital metaphors for understanding herself. The necessity of engaging with life in any fashion as a creative act, not as success or failure but as engagement, is continually reasserted.

In the film’s most important plot arc, Amélie engages in a romance with Nino Quincampoix (Mathieu Kassovitz) that is expressed through those fragments of the world with which both of them are obsessed, possessing as they do very similar sensibilities, but radically different attitudes. Where Amélie as a child was lonely, Nino was harassed. Where Amélie plays god, looking down on the world from rooftops, Nino is happy to make fetishes of the traces left by everyday human actions—footprints and torn-up railway station photographs, rolling on the dirty floor in his attempts to retrieve them. Amélie expresses herself in do-gooding, Nino does so in dressing as a fun fair ghoul and scaring people. Amélie, a waitress, is scared of and unfulfilled by intimacy, whilst Nino works in a porn store, scared of and unfulfilled by intimacy. Their opposing traits nonetheless revolve around a shared sense of the world both as friendly—Nino is as beloved as a hopeless romantic and weirdo by his friends as Amélie is by hers—and alienating, something that can only be safely approached from the outside through its detritus and busted hearts.

Nino, and through him Amélie, who recovers his scrapbook, had developed a fascination for a bald, unknown man whose pictures he regularly recovered from the photography booths. This man becomes emblematic of the vast mystery of life both Nino is trying to perceive and Amélie is trying to master. In the end, only she can lead Nino to the simple realisation that the mystery man is the repairman for the photography booths. Amélie engages Nino’s fascination for a kind of semaphore of attraction that manifests through recapitulating the substance of things. And yet Dufayel continually prods Amélie to remember that she can only get what she wants by finally leaving her cocoon of fancy and taking the risk of having her heart busted. In the very opening, Amélie is conceived at the same moment one man scratches the name of his deceased best friend from his address book, and Amélie’s “destiny” is set in play by the death of Princess Diana. Jeunet presents and represents life as being filled with ellipses and imperfect mirrors, and the possibility of one’s heart dying long before one’s body looms underneath Amélie’s antics. Such are the ways in which Jeunet complicates a nominally blithe tale of a waifish Samaritan who finds true love and “the pleasurable side of life,” as he called it.

With a different attitude in screenplay and direction, Amélie and Nino could be portrayed as sad and pathetic types, and yet Jeunet reveals the world through their innocent, but not foolish, eyes. Amélie’s dedication to adding to the happiness of the lives of others confirms not only personal, but communal love as an apex of happiness. The narrative attempts not simply to inspire happiness, but to ask what a pursuit of happiness may involve, proposing finally that whilst romantic companionship is the summit of Amélie’s ambitions, that companionship is inextricably linked with her outsider, observational, artistic nature. Amélie’s actions ennoble not only herself but also her corner of the universe, whilst also giving her the tools to perceive her future mate who would otherwise remain completely invisible. Fate is, finally, on Amélie’s side, too. If Truffaut’s Jules et Jim is “tragic” and Amélie is “feel-good,” Jeunet’s self-conscious flourishes confirm it as a consciously enforced choice—portraying the reality of alienation and frustrated desire as well the transformative capacity of art, love, and communal relationship. Whilst one may feel good at the end of Amélie, its breadth of offered life is both polished with finesse and multitudinous, the result of which confirms that part of achieving happiness is to face down what threatens to destroy us.

Although I adored Amelie, I preferred Jeunet’s older work such as Delicatessen, and even his new work Mic Macs. Amelie was a crowd-pleasing masterpiece, but his true gift is combing the dark recesses of the human soul through humor. Great review, thanks!

LikeLike

Zack, the non-critical tilt of this commentary, which was written initially as an academic essay, might suggest I’m a bigger fan of Amelie than I really am, but I concur that Jeunet’s earlier work was for me far more compelling; perhaps Marc Caro was the bigger influence on the darker hues of Delicatessan and City of Lost Children, although it did strike me how much more engaged A Very Long Engagement seemed to be whenever Marion Cotillard’s feline assassin was the focus, rather than the drippy leads. So perhaps Jeunet needs to liberate that irresponsible side of himself again.

LikeLike

Well said.

LikeLike