Amélie might be said to be a manifesto of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s philosophy of film-making and storytelling. All the trends that can be incidentally found in Jeunet’s other movies are here presented as the film’s central themes.

Jeunet’s movies have always been about finding pleasure in small things, and noticing the little details around us which other people miss. Here he has a heroine and other characters who make a virtue out of those qualities. Characters are introduced with a montage describing their likes and dislikes, covering everything from piercing the crust of crème brûlée with a spoon to watching a bullfighter getting gored.

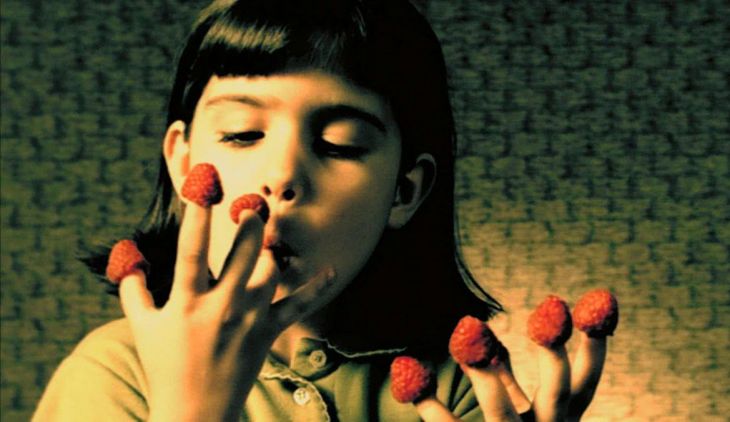

Trivial incidents that happened on particular dates are drawn to our attention – nuns playing basketball, for example. Jeunet is said to have been collecting the little impressions and events that make up Amélie since 1974. The opening credit sequence is a montage of the growing Amélie performing childish activities – playing with dominoes, making music with glasses, eating raspberries from her fingers etc.

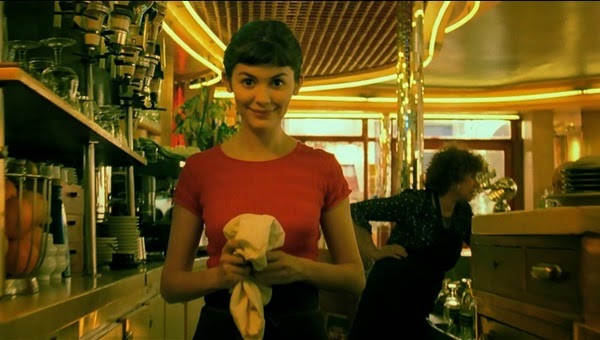

Another notable feature of Jeunet’s films is that they are populated with oddballs, misfits and outcasts – only this time the heroine’s individuality and isolation are what the movie is about. How does one find love and companionship in the bustle of modern society, especially when one does not fit in? “Times are hard for dreamers,” one character says.

The familiar visual trickery that makes up a Jeunet film therefore seems well-suited to the fantastical theme of the story. Amélie is not a fantasy as such, yet it often feels like one. Amélie Poulain has long flights of elaborate daydreaming, every image of which is shown to us visually. The unreal quality is added to by the constant camera tricks – montages, captions and arrows appearing on the screen, CGI, rapid zooms and cross-cutting.

Scenes are speeded up or slowed down. Fake TV footage is employed. The film is shot in hues of green, yellow and red, but some flashbacks and fantasies play out in black-and-white. Passport photos have conversations with one another, and a bedside lamp in the shape of a pig shakes its head sadly before turning off the light.

Despite the many modern techniques, Jeunet also uses the old-fashioned device of having a narrator tell the story. He is insistently present for the first part of the story, and thankfully slips into the background as the film progresses. There is also the elegant and wistful French music, often waltzes, that gives the film a traditional feel.

In line with the fantastical approach towards reality, Jeunet offers a sanitised vision of France. Before filming the outdoors scenes, he had the paths swept clean of litter and dirt. Some critics have complained about a certain ethnic cleansing too. Jeunet’s Paris is largely white, they argue, and not the diverse society it really is.

There are ethnic minorities in Amélie. Lucien is played by Jamel Debbouze, an actor of Moroccan descent. The photo album that plays an important part in the story also features people from different ethnic backgrounds. Perhaps Jeunet could have done more to capture the richness of Paris’s society though.

Merely hearing the storyline of Amélie was enough to set many people’s teeth on edge. As summarised at the time, it does indeed sound dreadful. A young woman is inspired by the death of Lady Diana (former Princess of Wales) to perform good deeds for others. How twee! How sentimental! How cloying!

This might have seemed particularly irritating for a number of my fellow-British people at the time when the film was made. The untimely death of Lady Diana inspired a widespread outpouring of public grief. However among some British people, there was a backlash against this attempt to present the former princess as if she was a saint.

The very newspapers that had been criticising her on the day before her death were writing hagiographies the next day. Politicians and musicians were quick to cash in on her death with mawkish tributes to ‘The People’s Princess’. Much of the hostility expressed against Diana was just as exaggerated as the absurd levels of praise heaped on her. Lady Di was a flawed public figure and not an angel, but her early death was certainly tragic.

To judge Amélie harshly because of associations with Lady Di is probably unfair. There are a number of allusions to Lady Di in the movie, and we might consider it to be infected with the general spirit of the time brought on by Diana’s death. However Amélie Poulain (Audrey Tautou) is not inspired to be a do-gooder by Diana, except in an indirect way.

Amélie is watching the news coverage of Diana’s death when an accident causes her to discover an old toy box owned by a boy who lived in the house many years ago. She decides to find the boy who hid the box in her apartment many years ago, and return the box to him. If he is overjoyed by the discovery, she will dedicate herself to good deeds.

The boy is now a grandfather. When Amélie finds Dominique Bretodeau (Maurice Bénichou), he is a lonely man. The sight of the box encourages him to seek reconciliation with his daughter, and thus Amélie’s vocation as a do-gooder is established.

Other deeds follow. Amélie’s concierge Madeleine Wallace (Yolande Moreau) is still mourning the death of her husband who had left her for another woman, so Amélie seeks to console the broken-hearted widow by faking letters, supposedly written by Madeleine’s husband before his death, in which he repents having left Madeleine.

Amélie also engages in some matchmaking between one of her work colleagues, the neurotic hypochondriac Georgette (Isabelle Nanty) and Joseph (Dominique Pinon), a former lover of their fellow waitress Gina (Clotilde Mollet). Joseph spends most of his day in the café spying on Gina and recording her interactions on a tape recorder until he is diverted to Georgette by Amélie. This leads to an off-screen sex scene that causes the glasses and bottles in the café to shake, recalling a similar moment in Jeunet’s earlier movie, Delicatessen.

Not all of Amélie’s schemes work out well. One of them goes wrong in a manner that seems (with hindsight) inevitable. Not all of her plots are kind. Some have a hint of malice about them. A neighbour convinces the young Amélie that her camera is responsible for a car crash on the street. Amélie avenges herself by climbing on his roof while he is watching football, and pulling out the television arial every time there is a goal.

In later life, Amélie is outraged by the unkind manner in which the greengrocer Collignon (Urbain Cancelier) treats his slow assistant, Lucien (Jamel Debbouze). After she obtains a key to Collignon’s apartment, Amélie enters the place while he is at work, and subtly alters household items to give him a scare.

Even Amélie’s actions to encourage her father to take up travelling have a hard edge to them. Angry that her father pays more attention to his garden gnome than he does to her, she arranges for the gnome to disappear. Soon Poulain (Rufus) receives postcards, supposedly from the gnome, showing pictures of the gnome visiting international tourist sites.

What is notable about all of these ingenious ‘stratagems’, as Amélie calls them, is that they are not intimate acts of kindness. They are done covertly without the recipients having any knowledge of what has been done for them. Here we get closer to the heart of the movie. Amélie is not about a young woman performing good deeds, but about a lonely woman who is unable or unwilling to interact with others.

Viewed in this way, Amélie’s kind actions are a substitute for the lack of love and warmth in her own life, and she is concerned with fixing the messes of other people’s life so that she does not have to fix the mess of her own. She is helping others to deflect from addressing her own fear of engaging with others. She feels safer in her world of fantasy than she does in dealing with the complicated world of real relationships.

That at least is the opinion of Amélie’s friend, Raymond Dufayel (Serge Merlin). Known as the Glass Man, Dufayel suffers from brittle bones and is unable to leave his apartment. Amélie seeks to bring the outside world to Dufayel by recording unusual items that she sees on television and sending the tapes to him. In return Dufayel offers her a dose of reality, and asks kind but searching questions about her life.

Their medium for discussing this is Renoir’s painting, Luncheon of the Boating Party. Dufayel is repainting this, but he cannot get the features of one of the women in the picture right. In their discussions, Amélie projects her own motives onto the missing figure, and Dufayel offers a critical analysis of those motives.

Amélie’s isolation from others, part-choice and part-circumstances is seen to stem from her relationship with her parents as a child. Her father is an ‘iceberg’ and her mother a neurotic. The only physical contact Amélie had with her father (a doctor) is during her medical check-up. This rare physical contact causes her heart to beat faster, convincing him she had a heart condition.

As a result, Amélie is home-schooled by her mother until her mother meets a comically unpleasant death. Deprived of love from her parents and removed from the company of other children, she has retreated into a world of the imagination, and fears what will happen when reality comes into contact with this world, and she has to deal with the affection of others. “I am nobody’s little weasel,” she tells her concierge.

The real focus of Amélie is not her do-gooding, but her attempts to seek a romantic bond with a young man, Nino Quicampoix (Mathieu Kassovitz). Nino is a male version of Amélie, only it was bullying at school that caused him to withdraw from others. He has his own quirks, and it is one of these that introduces him to Amélie.

Nino collects discarded passport photos from the area around the photo booth. (Before that he collected footprints and people’s laughs.) After he drops his photo album, Amélie has a chance to return the album to him. There is also a mystery concerning a mysterious man who regularly takes photographs of himself in the booths across Paris and then discards them. Is he a ghost, as Amélie speculates? (There is an amusing solution to this mystery, which I won’t reveal.)

Amélie is initially unnerved when she learns that Nino works in a sex shop, but this is in keeping with the difficulty that a strange man has in finding employment. He also works on the ghost train at a funfair, and was previously a department store Santa. Times are hard for dreamers.

There follows a series of ‘stratagems’ in which Amélie tries to woo Nino without ever properly meeting him. Her nerve fails when faced with reality. After she pretends not to recognise him when he visits her café, we see her literally dissolve into a pool of water, reflecting her distress.

The difficulty of creating characters who are too romantic and idealised to be real is that it is hard to imagine what they would be like if they ever got together in the end. That is why many fictional romances end in tragedy or separation.

Jeunet finds another solution. His two lovers barely ever speak. Their most sensual moment in the film is when Amélie takes a ride on the ghost train where Nino works, and he appears dressed as a ghost and caresses her neck. The final inevitable meeting of the lovers is wordless, and they do not speak thereafter. They may have finally faced up to reality together, but the audience is spared the need to do the same.

As a film Amélie had a curious opening reception. It was ignored by Cannes Film Festival, and yet it went on to become the highest grossing French film released in America. There is even a species of frog named after Amélie.

This reflects the traditional response to a Jeunet movie – some niche or populist appeal with audiences set against the lofty contempt of the serious film critics. Perhaps the film is too happy and cheerful to please many film buffs, who associate lightness with triviality. Perhaps it is difficult to analyse and admire a film that is as clear and pellucid as the pools on which Amélie enjoys skimming stones. What work is left for the analytical critic when the meaning is already on the surface, and accessible to every viewer on a first watch?

I had been an admirer of Jeunet’s work after I had seen Delicatessen ten years earlier. The popularity of Amélie actually curbed my initial appreciation of the film. It was rather like seeing a cult independent band suddenly making a mainstream album, and becoming known to everyone for the first time. Somehow there is always that hankering for the work that was made before it became too ‘commercial’.

After overcoming this feeling, I began to enjoy Amélie on its own merits. Jeunet’s style will repel as many people as it draws, but Amélie crams more imaginative and inventive detail into 15 minutes than many Hollywood blockbusters fit into two or three hours.

One thought on “Amélie (2001) ”