On my 16th birthday, my father gave me a painting of a plantation to remind me what our family had lost in the War Against Northern Aggression, as my family always insisted on calling it. Before I majored in American history at college, I hung it proudly as a sign of my father’s love and my family heritage.

But when I moved eight years later, I put it in the dusty attic, where it rested along with my feelings about American’s relationship with its racist past. At times, thoughts of my family’s history haunted me much like the painting, and I wondered if most white Americans felt like me, or simply shoved these feelings into the furthest corners of their minds and homes. This Black History Month, as we look across a divided America, we white Americans would do well to take a look at our past and the things we hide in our dusty attics. Looking squarely at what we’ve done might help heal the divide.

Some of my family think that the past is the past and that our ancestor’s crimes are their own, not ours to atone for. I see it differently.

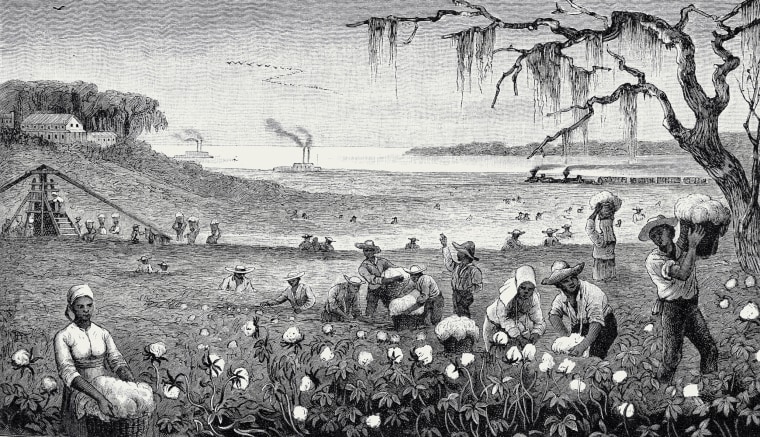

White Americans enslaved kidnapped Africans. My ancestors settled on lands once belonging to Native Americans. Plantation masters like my French ancestors raped, tortured and tore families apart, all for the sake of their wealth and a financial “system” long deemed irrelevant in the North. Whereas white Americans can see plantations as beautiful, picturesque estates on which to hold weddings and other celebrations, we often miss how black America views these monuments to the past. The elegant oak trees with their hanging Spanish moss may look picture-perfect to a Caucasian, but to someone with African, Native or Latina roots, it may conjure ancestors hanging from those branches with that moss around them. White America may see the intricacies of French colonial architecture, whereas black America may see the generational traumas they have endured. Most of my family considers a movie such as “Gone With the Wind” as a depiction of truth that immortalizes the heroics of Scarlet O’Hara, rather than a problematic portrayal of the slaves who work for her.

I have long recognized that my family and I have grown apart over the years in ways both political and personal. We both support the police; however, I also support the Black Lives Matter movement and object to the over-policing and criminalizing of African Americans evident in cases like that of Sandra Bland, who died while in custody. When I tweeted in support of #SayHerName, a hashtag dedicated to supporting victims like Bland, my family stopped talking to me for a year. I am pro-choice, having gone through an abortion and become a clinic escort; they told others not to speak to me because I had turned my back on “their” ways. They own enough guns to take out a hoard of zombies; I shy away from guns, having been brutalized with a firearm by an ex-boyfriend years prior. They voted for Trump; I chose to cast my vote for anything other than a Republican Party that seems to thrive on Trumpian cruelty.

Some of my family think that the past is the past and that our ancestor’s crimes are their own, not ours to atone for. I see it differently. Genetic research suggests that past traumas might be encoded in our DNA. Therefore, how can one argue our ancestors’ crimes are their crimes alone? I learned in trauma therapy that to fully atone for the sins of the past, one must directly confront both the pain the aggressor caused and the pain in oneself to process it. But if so much of white America wants to ignore the trauma of our fellow citizens and ignore the anger it incites, how will we ever move forward?

It then dawned on me that dealing with past trauma starts in my own house, confronting the relics of paintings past and family demons packed deep away. The anniversary of my mother’s death a few years ago prompted me to engage with this history, and I recently texted some of the little family I have left after drugs, heart attacks and mental illness ravaged our lines. It had been a while since we were in touch, and the last thing anyone wanted to talk about with me was the past — or the part of it living in the political climate we now inhabit in America. Most were dealing with the fallout of the opioid crisis in their circles of the South. Still, I stuck to my own internal promise of dealing with the past and the message of that dusty painting.

To my great relief, the response I got was for the most part promising, a welcome change compared to the attitudes I encountered growing up. My father, once a proud son of the South and the patriarchal head of our little family, had changed the most. Before, my father was a proud man even when he was wrong. Now he seemed OK with letting the past be the past, and accepting that what happened was wrong, that we shouldn’t idolize a painting and a bygone era filled with pain. I had brought out the painting and was staring at it as I talked to him on the phone. He told me the painting was still mine to do with as I please. I wished him well and hung up, then wiped the dust off the broad brush strokes of the oak-lined drive and grand manor in the frame.

Today, the painting hangs in my study along with a photo I came across of a group of African American medical students wearing their pristine white medical coats at another old plantation. I tell myself each day as I write my great American novel that this is the United States we all should strive to see. Not the past, but the change and the promise of what can be, just like those young Americans in their pristine lab coats ready to truly make America great by standing up to the past.