Sidney Poitier’s skill was that, more than almost any other actor of his time, he gave to audiences an essential reassurance; Poitier’s problem was that in the era of the Black Panthers, reassurance looked like collusion. He was the Martin Luther King character, entirely dignified, in contrast to Malcolm X, whose very persona was a sharp rebuff to worried whites. It was the paradox of his career that Poitier’s genius should be expressed in a culture that found consensus suspect. Yet the audience he won over was no homogeneous entity, but a crowd suffused with contention.

What we see in Poitier’s extraordinary run of movies, from The Defiant Ones (1958) to Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), is the record of a divided America’s growing desire to unite around their affection for this shyest of stars. Race complicates this bashful love; Poitier’s essential apartness as a person is what is being screened. At the inception of the permissive society, Poitier stood as the restrained, courteous and uncorrupted star, someone truly heroic. His reiterated attempt to express the dignity of an adult man is a social project, an assertion of the deepest possible civil right.

Poitier was the first black male star to engage the American national consciousness at a time when the prevailing image of a film star was still that of someone white. In a 1967 interview, Poitier declared that when he first began appearing in films, “the kind of Negro played on the screen was always negative, buffoons, clowns, shuffling butlers, really misfits. This was the background when I came along 20 years ago and I chose not to be a party to the stereotyping … I want people to feel when they leave the theatre that life and human beings are worthwhile. That is my only philosophy about the pictures I do … I have four children … They go to movies all the time but they rarely see themselves reflected there.”

It would be hard to overstate the strength and depth of the prejudices that an actor such as Poitier had to overcome. When she received an Oscar for best supporting actress for Gone With the Wind in 1940, Hattie McDaniels was made to sit at a separate table from the white cast. Given these attitudes, it’s extraordinary that, in a 1968 Motion Picture Herald poll, Poitier was named the No 1 money-making film star in the world. As the series of his films being screened as part of the BFI’s Black Star season demonstrate, the time was right for Poitier.

That time began with Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958), which has Poitier on the run from the chain gang, while handcuffed to a racist fellow con, played by Tony Curtis. On screen, Poitier was often paired up, even bound together, with racist characters. In Pressure Point (1962), he is a prison psychiatrist obliged to treat a pathologically racist American Nazi (played by Bobby Darin). The Defiant Ones displays a strange fascination with the physical proximity of the two men, a closeness always threatening to turn to violence. It’s a staging of a baffled and beguiling closeness between black and white characters that will run through many of Poitier’s greatest films.

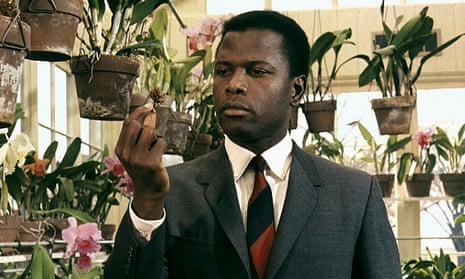

In A Raisin in the Sun (1961), Poitier is firmly at home with a mainly black cast, a thwarted son and husband blocked in his attempt to step out of the ghetto. Poitier here can define himself in relation to other African-American characters, a route to maturity he was rarely offered in his best films. Poitier’s greatest role, and the one for which he won a Golden Globe and an Oscar, is Homer Smith in Ralph Nelson’s stirring Lilies of the Field (1963). It’s hard to think of a less fashionable film; no movie that ends with a hymn and a resounding “Amen” is likely to be popular again. Poitier is a drifter who finds himself taken in by a group of German-speaking nuns eager to have him build them a chapel in the middle of the Arizona desert. Lilies of the Field creates a utopian space, remote as it can be from racist contempt, establishing a realm for hard‑working migrants. The only person in the film to express racist views is a middle-aged white boss; it’s a movie made to foster agreement. That last “Amen” is apt in a parable about coming together, reaching accord. In Guy Green’s A Patch of Blue (1965), Poitier plays an office clerk who decides to help a young blind woman, someone who has been confined to her room by her manipulative mother (an Oscar-winning performance by Shelley Winters). Set in a racist southern city, it’s a kind of fable about race relations. As Selina (Elizabeth Hartman) is blind, she only notices Poitier’s kindness, humour and concern, and when she discovers he is black, she does not stop loving him. Her mother is a prostitute, and Selina ends up being pushed into prostitution herself. It’s a grimly sexualised world, and amid its voyeuristic complicities, only Poitier seems to stand above the ruthlessness of desire.

In his 1950s and 60s movies, Poitier was not allowed to display much, if any, evidence of sexuality. At the time, some critics worried that his character’s apparent lack of sexual interest in Selina was a cop-out, a refusal to own up to adult facts. Certainly, there was an investment in imagining Poitier as chaste. The reassurance he offers is itself “sexy”, I feel, though in part because it transcends the possibility of actual sex. That sexiness would be most at issue, perhaps, in his playing the charismatic school teacher in the British film directed by James Clavell To Sir, With Love (1967), where the circumstances insist on Poitier’s wistful avoidance of his pupil Judy Geeson’s schoolgirl crush. Here his self-imposed restraint makes sense, and undoubtedly if he flirted back or responded in kind, we’d think less of him. The film makes explicit the ways in which Poitier’s movies preoccupy themselves with the exploration of his on-screen appeal. Playing one of his young East End pupils, Lulu speculates: “You’re like us, but you ain’t.” Poitier was always “like us”, while being in indefinable ways better: more courteous, more courageous. He places himself here on one side of the generation gap, standing in for an authority that youth might still respect. (A dozen years before, Poitier had himself played a classroom hooligan in Blackboard Jungle .)

In his other two great films of 1967, In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Poitier is more firmly on the boundary between the two generations. In the first, he is at once an earnest policeman and an example of young African-American self-assertion; in the second, he is a mature doctor and a rebellious son. It’s clear from all three 1967 films how much Poitier became necessary as a way to figure a route out of the conflict in American life. He was on both sides at once, not as a dupe or an “Uncle Tom”, but as a genuinely responsible, realised man.

Poitier recently won a BFI poll for the best ever performance by a black actor for his role as Virgil Tibbs in Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night. It’s certainly one of his best films, though in terms of his acting, it’s remarkable chiefly for how fiercely he puts himself in abeyance. His restraint is what’s on show, and it is more than ever a film about our distance and closeness to the star. Three times, our hero tenderly touches the white characters, crossing an indefinable borderline. We see it in the compassionate attentiveness with which he examines the murder victim’s body; it’s there in the careful grasp with which he caresses the first major suspect; it’s present most tentatively in the restrained touch with which he endeavours to comfort the grieving widow. It’s a film about needing help, and the detective plot is a mere McGuffin around those touches and the sympathetic reaching out enacted between bullish, put-upon Rod Steiger and Poitier. The parody of these intimacies comes with the returned slap that Poitier gives to the racist plantation owner. That hard blow shows he’s no cheek-turning Christian but a person asserting himself in the world. Watching Poitier’s films, I lost count of the moments where white characters call him “boy”. With that in mind, the simple statement, “They call me Mr Tibbs”, is a declaration of independence.

If we want to place these touches in context, it is good to remember the scandal caused in March 1968, when Petula Clark touched Harry Belafonte’s arm on television, or the furore around the first TV “interracical” kiss that November, between Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhuru and Captain Kirk. Only in 1967 did the US supreme court unanimously rule that anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional. There was a taboo on tenderness: the feelings inspired by Poitier had to remain attenuated, distanced ones. It’s especially good to bear all this in mind when watching Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, a cotton-wool unreality of a movie. Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy’s bubbly innocent daughter is set to marry Poitier, a widowed older doctor; his parents, and hers, are unhappy about it. It’s not that they are racist, the film tells us, more that they worry about the problems and prejudices such a couple will face. In the end, naturally, love conquers all. The movie’s real subject is again the generational divide, with Poitier a 37-year-old who is still primarily a son. He stands up for the younger generation, declaring to his father: “You think of yourself as a coloured man, I think of myself as a man.” It was, in its way, Poitier’s last great statement of belief, an assertion of his right to be a person on film.

After the great year of 1967, he kept making movies, but nothing ever again matched the impact and power of the films he had made in the previous 10 years. He trod old ground, reprising the role of Tibbs, twice, and even doing the TV film To Sir, With Love II; he played Nelson Mandela alongside Michael Caine as FW de Klerk, and was as good as ever. Yet, US cinema could no longer find a significant place for him. Still, the impact of those movies and the ways they changed American life are being felt today. In these films, Poitier will always be a living example of a star and of a good man, an actor carrying movie stardom and even the idea of personhood itself forward through a period of profound change.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion