“I am the author, or one of the authors, of the new Russian system,” Vladislav Surkov told us by way of introduction. On this spring day in 2013, he was wearing a white shirt and a leather jacket that was part Joy Division and part 1930s commissar. “My portfolio at the Kremlin and in government has included ideology, media, political parties, religion, modernization, innovation, foreign relations, and ...”—here he pauses and smiles—“modern art.” He offers to not make a speech, instead welcoming the Ph.D. students, professors, journalists, and politicians gathered in an auditorium at the London School of Economics to pose questions and have an open discussion. After the first question, he talks for almost 45 minutes, leaving hardly any time for questions after all.

It’s his political system in miniature: democratic rhetoric and undemocratic intent.

As the former deputy head of the presidential administration, later deputy prime minister and then assistant to the president on foreign affairs, Surkov has directed Russian society like one great reality show. He claps once and a new political party appears. He claps again and creates Nashi, the Russian equivalent of the Hitler Youth, who are trained for street battles with potential pro-democracy supporters and burn books by unpatriotic writers on Red Square. As deputy head of the administration he would meet once a week with the heads of the television channels in his Kremlin office, instructing them on whom to attack and whom to defend, who is allowed on TV and who is banned, how the president is to be presented, and the very language and categories the country thinks and feels in. Russia’s Ostankino TV presenters, instructed by Surkov, pluck a theme (oligarchs, America, the Middle East) and speak for 20 minutes, hinting, nudging, winking, insinuating, though rarely ever saying anything directly, repeating words like “them” and “the enemy” endlessly until they are imprinted on the mind.

They repeat the great mantras of the era: The president is the president of “stability,” the antithesis to the era of “confusion and twilight” in the 1990s. “Stability”—the word is repeated again and again in a myriad seemingly irrelevant contexts until it echoes and tolls like a great bell and seems to mean everything good; anyone who opposes the president is an enemy of the great God of “stability.” “Effective manager,” a term quarried from Western corporate speak, is transmuted into a term to venerate the president as the most “effective manager” of all. “Effective” becomes the raison d’être for everything: Stalin was an “effective manager” who had to make sacrifices for the sake of being “effective.” The words trickle into the streets: “Our relationship is not effective” lovers tell each other when they break up. “Effective,” “stability”: No one can quite define what they actually mean, and as the city transforms and surges, everyone senses things are the very opposite of stable, and certainly nothing is “effective,” but the way Surkov and his puppets use them the words have taken on a life of their own and act like falling axes over anyone who is in any way disloyal.

One of Surkov’s many nicknames is the “political technologist of all of Rus.” Political technologists are the new Russian name for a very old profession: viziers, gray cardinals, wizards of Oz. They first emerged in the mid-1990s, knocking on the gates of power like pied pipers, bowing low and offering their services to explain the world and whispering that they could reinvent it. They inherited a very Soviet tradition of top-down governance and tsarist practices of co-opting anti-state actors (anarchists in the 19th century, neo-Nazis and religious fanatics now), all fused with the latest thinking in television, advertising, and black PR. Their first clients were actually Russian modernizers: In 1996 the political technologists, coordinated by Boris Berezovsky, the oligarch nicknamed the “Godfather of the Kremlin” and the man who first understood the power of television in Russia, managed to win then-President Boris Yeltsin a seemingly lost election by persuading the nation that he was the only man who could save it from a return to revanchist Communism and new fascism. They produced TV scare-stories of looming pogroms and conjured fake Far Right parties, insinuating that the other candidate was a Stalinist (he was actually more a socialist democrat), to help create the mirage of a looming “red-brown” menace.

In the 21st century, the techniques of the political technologists have become centralized and systematized, coordinated out of the office of the presidential administration, where Surkov would sit behind a desk with phones bearing the names of all the “independent” party leaders, calling and directing them at any moment, day or night. The brilliance of this new type of authoritarianism is that instead of simply oppressing opposition, as had been the case with 20th-century strains, it climbs inside all ideologies and movements, exploiting and rendering them absurd. One moment Surkov would fund civic forums and human-rights NGOs, the next he would quietly support nationalist movements that accuse the NGOs of being tools of the West. With a flourish he sponsored lavish arts festivals for the most provocative modern artists in Moscow, then supported Orthodox fundamentalists, dressed all in black and carrying crosses, who in turn attacked the modern-art exhibitions. The Kremlin’s idea is to own all forms of political discourse, to not let any independent movements develop outside of its walls. Its Moscow can feel like an oligarchy in the morning and a democracy in the afternoon, a monarchy for dinner and a totalitarian state by bedtime.

* * *

Surkov is more than just a political operator. He is an aesthete who pens essays on modern art, an aficionado of gangsta rap who keeps a photo of Tupac on his desk next to that of the president.

And he is also the alleged author of a novel, Almost Zero, published in 2008 and informed by his own experiences. “Alleged” because the novel was published under the pseudonym Natan Dubovitsky; Surkov’s wife is named Natalya Dubovitskaya. Officially Surkov is the author of the preface, in which he denies being the author of the novel, then makes a point of contradicting himself: “The author of this novel is an unoriginal Hamlet-obsessed hack”; “this is the best book I have ever read.” In interviews he can come close to admitting to being the author while always pulling back from a complete confession. Whether or not he actually wrote every word of it, he has gone out of his way to associate himself with it. And it is a bestseller: the key confession of the era, the closest we might ever come to seeing inside the mind of the system.

The novel is a satire of contemporary Russia whose hero, Egor, is a corrupt PR man happy to serve anyone who’ll pay the rent. A former publisher of avant-garde poetry, he now buys texts from impoverished underground writers, then sells the rights to rich bureaucrats and gangsters with artistic ambitions, who publish them under their own names. Everyone is for sale in this world; even the most “liberal” journalists have their price. The world of PR and publishing as portrayed in the novel is dangerous. Publishing houses have their own gangs, whose members shoot each other over the rights to Nabokov and Pushkin, and the secret services infiltrate them for their own murky ends. It’s exactly the sort of book Surkov’s youth groups burn on Red Square.

Born in provincial Russia to a single mother, Egor grows up as a bookish hipster disenchanted with the late Soviet Union’s sham ideology. In the 1980s he moves to Moscow to hang out on the fringes of the bohemian set; in the 1990s he becomes a PR guru. It’s a background that has a lot in common with what we know of Surkov’s own—he only leaks details to the press when he sees fit. He was born in 1964, the son of a Russian mother and a Chechen father who left when Surkov was still a young child. Former schoolmates remember him as someone who made fun of the teacher’s pets in the Komsomol, wore velvet trousers, had long hair like Pink Floyd, wrote poetry, and was a hit with the girls. He was a straight-A student whose essays on literature were read aloud by teachers in the staff room; it wasn’t only in his own eyes that he was too smart to believe in the social and political set around him.

“The revolutionary poet Mayakovsky claimed that life (after the communist revolution) is good and it’s good to be alive,” wrote the teenage Surkov in lines that were strikingly subversive for a Soviet pupil. “However, this did not stop Mayakovsky from shooting himself several years later.”

After he moved to Moscow, Surkov first pursued and abandoned a range of university careers from metallurgy to theater directing, then put in a spell in the army (where he might have served in military espionage), and engaged in regular violent altercations (he was expelled from drama school for fighting). His first wife was an artist famous for her collection of theater puppets (which Surkov would later build up into a museum). And as Surkov matured, Russia experimented with different models at a dizzying rate: Soviet stagnation led to perestroika, which led to the collapse of the Soviet Union, liberal euphoria, economic disaster, oligarchy, and the mafia state. How can you believe in anything when everything around you is changing so fast?

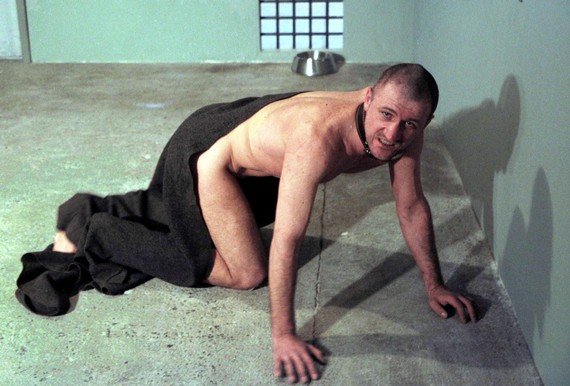

He was drawn to the bohemian set in Moscow, where performance artists were starting to capture the sense of dizzying mutability. No party would be complete without Oleg Kulik (who would impersonate a rabid dog to show the brokenness of post-Soviet man), German Vinogradov (who would walk naked into the street and pour ice water over himself), or later Andrej Bartenjev (who would dress as an alien to highlight how weird this new world was). And of course Vladik Mamyshev-Monroe. Hyper-camp and always playing with a repertoire of poses, Vladik was a post-Soviet Warhol mixed with RuPaul. Russia’s first drag artist, he started out impersonating Marilyn Monroe and Hitler (“the two greatest symbols of the 20th century,” he would say) and went on to portray Russian pop stars, Rasputin, and Gorbachev as an Indian woman; he turned up at parties as Yeltsin, Tutankhamen, or Karl Lagerfeld. “When I perform, for a few seconds I become my subject,” Vladik liked to say. His impersonations were always obsessively accurate, pushing his subject to the point of extreme, where the person’s image would begin to reveal and undermine itself.

At the same time, Russia was discovering the magic of PR and advertising, and Surkov found his métier. He was given his chance by Russia’s best-looking oligarch, Mikhail Khodorkovsky. In 1992 he launched Khodorkovsky’s first ad campaign, in which the oligarch, in checked jacket, mustache, and a massive grin, was pictured holding out bundles of cash: “Join my bank if you want some easy money” was the message. “I’ve made it; so can you!” The poster was pinned up on every bus and billboard, and for a population raised on anti-capitalist values, it was a shock. It was the first time a Russian company had used the face of its own owner as the brand. It was the first time wealth had been advertised as a virtue. Previously millionaires might have existed, but they always had to hide their success. Surkov could sense the world was shifting.

Surkov next worked as head of PR at Ostankino’s Channel 1, for the then-grand vizier of the Kremlin court, Boris Berezovsky. In 1999 he joined the Kremlin, creating the president’s image just as he had created Khodorkovsky’s. When the president exiled Berezovsky and arrested and jailed Khodorkovsky, Surkov helped run the media campaign, which featured a new image of Khodorkovsky: instead of the grinning oligarch pictured handing out money, he was now always shown behind bars. The message was clear—you’re only a photo away from going from the cover of Forbes to a prison cell.

And through all these changes, Surkov switched positions, masters, and ideologies without seeming to skip a beat.

Perhaps the most interesting parts of Almost Zero occur when the author moves away from social satire to describe the inner world of his protagonist. Egor is described as a “vulgar Hamlet” who can see through the superficiality of his age but is unable to have genuine feelings for anyone or anything: “His self was locked in a nutshell ... outside were his shadows, dolls. He saw himself as almost autistic, imitating contact with the outside world, talking to others in false voices to fish out whatever he needed from the Moscow squall: books, sex, money, food, power, and other useful things.”

Egor is a manipulator but not a nihilist; he has a very clear conception of the divine: “Egor could clearly see the heights of Creation, where in a blinding abyss frolic non-corporeal, un-piloted, pathless words, free beings, joining and dividing and merging to create beautiful patterns.”

The heights of creation! Egor’s god is beyond good and evil, and Egor is his privileged companion: too clever to care for anyone, too close to God to need morality. He sees the world as a space in which to project different realities. Surkov articulates the underlying philosophy of the new elite, a generation of post-Soviet supermen who are stronger, more clearheaded, faster, and more flexible than anyone who has come before.

When I worked in Russian television, I encountered forms of this attitude every day. The producers who worked at the Ostankino channels might all be liberals in their private lives, holiday in Tuscany, and be completely European in their tastes. When I asked how they married their professional and personal lives, they looked at me as if I were a fool and answered: “Over the last 20 years we’ve lived through a communism we never believed in, democracy and defaults and mafia state and oligarchy, and we’ve realized they are illusions, that everything is PR.”

“Everything is PR” has become the favorite phrase of the new Russia; my Moscow peers were filled with a sense that they were both cynical and enlightened. When I asked them about Soviet-era dissidents, like my parents, who fought against communism, they dismissed them as naive dreamers and my own Western attachment to such vague notions as “human rights” and “freedom” as a blunder. “Can’t you see your own governments are just as bad as ours?” they asked me. I tried to protest—but they just smiled and pitied me. To believe in something and stand by it in this world is derided, the ability to be a shape-shifter celebrated.

Vladimir Nabokov once described a species of butterfly that at an early stage in its development had to learn how to change colors to hide from predators. The butterfly’s predators had long died off, but still it changed its colors from the sheer pleasure of transformation. Something similar has happened to the Russian elites: During the Soviet period they learned to dissimulate in order to survive; now there is no need to constantly change their colors, but they continue to do so out of a sort of dark joy, conformism raised to the level of aesthetic act.

Surkov himself is the ultimate expression of this psychology. As I watched him give his speech to the students and journalists in London, he seemed to change and transform like mercury, from cherubic smile to demonic stare, from a woolly liberal preaching “modernization” to a finger-wagging nationalist, spitting out willfully contradictory ideas: “managed democracy,” “conservative modernization.” Then he stepped back, smiling, and said: “We need a new political party, and we should help it happen, no need to wait and make it form by itself.” And when you look closely at the party men in the political reality show Surkov directs, the spitting nationalists and beetroot-faced communists, you notice how they all seem to perform their roles with a little ironic twinkle.

Surkov likes to invoke the new postmodern texts just translated into Russian, the breakdown of grand narratives, the impossibility of truth, how everything is only “simulacrum” and “simulacra” ... and then in the next moment he says how he despises relativism and loves conservatism, before quoting Allen Ginsberg’s “Sunflower Sutra,” in English and by heart. If the West once undermined and helped to ultimately defeat the U.S.S.R. by uniting free-market economics, cool culture, and democratic politics into one package (parliaments, investment banks, and abstract expressionism fused to defeat the Politburo, planned economics, and social realism), Surkov’s genius has been to tear those associations apart, to marry authoritarianism and modern art, to use the language of rights and representation to validate tyranny, to recut and paste democratic capitalism until it means the reverse of its original purpose.

* * *

“It was the first non-linear war,” writes Surkov in a new short story, “Without Sky,” published under his pseudonym and set in a dystopian future after the “fifth world war”:

In the primitive wars of the 19th and 20th centuries it was common for just two sides to fight. Two countries. Two groups of allies. Now four coalitions collided. Not two against two, or three against one. No. All against all.

There is no mention of holy wars in Surkov’s vision, none of the cabaret used to provoke and tease the West. But there is a darkling vision of globalization, in which instead of everyone rising together, interconnection means multiple contests between movements and corporations and city-states—where the old alliances, the EUs and NATOs and “the West,” have all worn out, and where the Kremlin can play the new, fluctuating lines of loyalty and interest, the flows of oil and money, splitting Europe from America, pitting one Western company against another and against both their governments so no one knows whose interests are what and where they’re headed.

“A few provinces would join one side,” Surkov continues. “A few others a different one. One town or generation or gender would join yet another. Then they could switch sides, sometimes mid-battle. Their aims were quite different. Most understood the war to be part of a process. Not necessarily its most important part.”

The Kremlin switches messages at will to its advantage, climbing inside everything: European right-wing nationalists are seduced with an anti-EU message; the Far Left is co-opted with tales of fighting U.S. hegemony; U.S. religious conservatives are convinced by the Kremlin’s fight against homosexuality. And the result is an array of voices, working away at global audiences from different angles, producing a cumulative echo chamber of Kremlin support, all broadcast on RT.

“Without Sky” was published on March 12, 2014. A few days later, Russia annexed Crimea. Surkov helped to organize the annexation, with his whole theater of Night Wolves, Cossacks, staged referendums, scripted puppet politicians, and men with guns. The Kremlin’s new useful allies, Right, Left, and Religious, all backed the president. There were no sanctions from the West that might have threatened economic ties with Russia. Only a few senior officials, including Surkov, were banned from traveling to or investing in the United States and European Union.

“Won’t this ban affect you?” a reporter asked Surkov as he passed through the Kremlin Palace. “Your tastes point to you being a very Western person.” Surkov smiled and pointed to his head: “I can fit Europe in here.” Later he announced: “I see the decision by the administration in Washington as an acknowledgment of my service to Russia. It’s a big honor for me. I don’t have accounts abroad. The only things that interest me in the U.S. are Tupac Shakur, Allen Ginsberg, and Jackson Pollock. I don’t need a visa to access their work. I lose nothing.”

This article has been adapted from Peter Pomerantsev’s forthcoming book Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible and draws on his work for the London Review of Books.