Four black female banjo players wrestling with gender, race, slavery, sexual assault and the domination of the male gaze might make an admirable-if-arduous prospect, but this new collaboration proves by turns a proud, devastating, authoritative album made for our bewildering times.

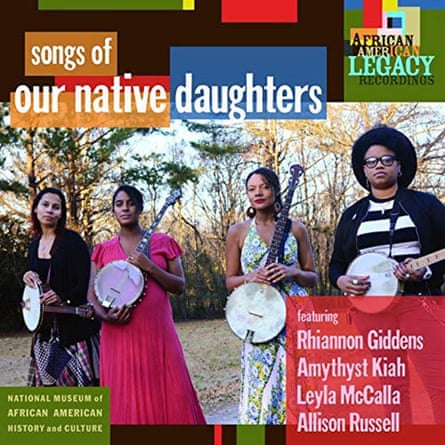

Our Native Daughters is a collaboration between the North American roots musicians Rhiannon Giddens, Leyla McCalla, Allison Russell and Amythyst Kiah. Of the four, Giddens holds the highest profile. Her solo work has been Grammy-nominated; Carolina Chocolate Drops, the old-time string band she co-founded, are Grammy winners. She is also a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship “genius grant” and the Steve Martin prize for excellence in bluegrass and banjo.

Her bandmates are less-widely feted, but have all crossed paths on the folk scene over the years. Kiah is an alt-country blues singer from Tennessee with a voice as rich as Tracy Chapman; McCalla is a Haitian American who draws on Creole and Cajun traditions and writes often of the modern socio-political divide; and Russell is a Canadian singer and multi-instrumentalist whose voice carries some of the flutter of Frazey Ford.

It was Giddens who started the project after time spent reading slave accounts in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, and fuelled by righteous fury after watching the 2016 film drama The Birth of a Nation, in which she noticed how a scene portraying the rape of a female slave on a plantation focused more on the reaction of her husband than the woman herself.

What she sought with Our Native Daughters was to shift the perspective. In the liner notes (which come with an accompanying bibliography), Giddens writes of how at the intersection of racism and sexism “stands the African American woman. Used, abused, ignored and scorned, she has in the face of these things been unbelievably brave, groundbreaking and insistent. Black women have historically had the most to lose, and have therefore been the fiercest fighters for justice.”

Among these 13 tracks, then, stand reinterpretations of slave and minstrel stories; personal tales of sexual abuse, suffering and survival; and accounts of remarkable female perseverance carried across time and geography. An ancestor sold into slavery from the coast of Ghana inspires Russell’s Quasheba, Quasheba, in which, above measured percussion and rueful strings, she sings of one “Raped and beaten / Every baby taken / But ain’t you a woman / Of love deservin’.”

There are nods too to musical predecessors –– the opening number Black Myself is Kiah’s contemporising of a Sid Hemphill song addressing intra-racial discrimination, while the story of Etta Baker, the Piedmont blues guitarist whose husband prevented her from playing until she was in her 60s, is captured on the steady fingerpicked number I Knew I Could Fly.

It makes for a hugely intimate portrayal in which, remarkably, the gravitas of the undertaking never outweighs its joy. Even on a track such as Mama’s Cryin’ Long, in which Giddens leads a child’s story of the rape of her mother, the subsequent stabbing of her attacker and the mother’s lynching, there is something pulsing and resonant in the congregation of voices coming around a spare, clapped rhythm that suggests resilience through the horror.

Frequently there is something deeply rousing in hearing these four female voices butt up against one another, weave around, stand aside, make space. Likewise their banjo-playing styles, which run from the five-string and tenor to the early fretless minstrel incarnation chosen by Giddens, serve as a reminder of the variation and nuance of an instrument somewhat besmirched by the new-folk scene.

In heavier hands, with less-gifted musicians, this project could surely have buckled under its worthiness. But what Giddens and her cohorts have managed to create is a record of great importance and exceptional beauty, its darker moments countered by points of bright wonder: the sprightliness and charge of album closer You’re Not Alone, for instance, or the extraordinary, twirling Moon Meets the Sun: “Oh you put the shackles on our feet but we’re dancing,” Giddens sings over a winding, uplit banjo line. “Oh you steal our very tongues but we’re dancing,” she continues, before summoning her companions: “Brown Girl in the ring,” she calls, “raise your voice and sing.”

Such displays of unity in an industry that often seeks to stoke rivalries between female performers are becoming increasingly common – Songs of Our Native Daughters follows recent collaborations between Neko Case, Laura Veirs and KD Lang, and by Phoebe Bridgers, Lucy Dacus and Julien Baker, and we should find great hope in that. It’s not a drowning out of the male voice, but a redressing, a powerful gathering of force in musical solidarity.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion